By Karen Lloyd AM

[Please scroll to the bottom for Auslan translation]

I’m worried about my community. While some deaf community members are celebrating the merger of Access Plus WA Deaf with Deaf Connect, many are not and many are afraid to comment publicly. I don’t believe it is in our best interests to have a big national organisation doing everything for us. I know there are others who agree with me but feel it isn’t safe to say anything. In the past, State Deaf Societies run by hearing people did everything for us. Now we have a very large national Deaf Society led by a deaf CEO and history is repeating itself in disturbing ways.

Deaf Connect and Access Plus WA Deaf were both previously known as Deaf Societies. Those of us older than about forty remember our old style Deaf Societies with affection. They were at the centre of our community. They were welfare charities funded by donations, bequests, fundraising and some government funding. They provided welfare support, interpreting, hostels and nursing homes, deaf social clubs, and a home for various community organisations – social, sporting, advocacy. They were our second home – safe deaf spaces. We especially loved our deaf clubs. I have many wonderful memories of Friday nights at Sydney’s Stanmore deaf club.

But not all was rosy within our Deaf Societies. Although some deaf people worked there, hearing people were in charge. They were paternalistic and controlling.

In the 1980s and early 1990s there were major, far-reaching changes. Auslan was recognised as a real language. The roles of welfare workers and interpreters were separated. The deaf community protested against ‘please help the poor deaf people’ fundraising messages. More deaf people began working at Deaf Societies and serving on their boards. Fundraising became harder and Deaf Societies relied more on government funding. They began to sell their large buildings, close their deaf clubs and move to a fee-for-service business model in smaller premises.

Australian Association of the Deaf (AAD – now Deaf Australia) was established in 1986. It is still the only national organisation in Australia that is wholly deaf-controlled, does not make money providing services to deaf people, and has deaf people’s interests as its first priority. In its early days Deaf Societies provided some funding until AAD succeeded in getting government funding. They worked in partnership, Deaf Societies mostly taking a supportive back seat while AAD led advocacy campaigns. The Deaf Society of NSW (DSNSW) provided practical help. Several of us attended residential leadership training programs organised and funded by DSNSW. In the early 1990s when I was secretary of AAD, the DSNSW CEO, Anne Mac Rae, taught me how to write funding submissions. She coached Dr Colin Allen AM, then president of AAD, and me to prepare for meetings with government and attended meetings with us until we were confident enough to go without her.

But Deaf Societies never totally relinquished advocacy and there were tensions in the relationship between them and AAD/Deaf Australia. During my 25 years of active involvement with AAD/Deaf Australia I had numerous meetings with Deaf Societies and I always left those meetings feeling like a naughty school girl – they wanted us to do things their way and we often disagreed.

The NDIS has brought more changes. It has brought a bonanza of new money and great opportunities for service providers to grow their business – and that has been their focus for the past ten years. Now funding comes to us individually and we buy the services we need. It is supposed to give us choice and control over our own lives. It’s supposed to move us away from the old model of one organisation doing everything for us.

But the NDIS is not currently fulfilling its promise and instead of seeing more diversity in service options, we are seeing less. Our State Deaf Societies have been merging and now we have only two: Deaf Connect, operating in Queensland, NSW, SA, ACT, NT and WA; and Expression Australia, operating in Victoria and Tasmania. Some new service providers have emerged but they tend to be small and specialised. It’s difficult for them to compete with the coverage, profile and money now commanded by Deaf Connect.

I am sure that from a business perspective there are valid reasons for these mergers. Some Deaf Societies struggled financially to provide services and to find competent CEOs who understand the deaf community. Deaf Connect is now a very healthy business.

From a community perspective, the mergers are understandable in some ways. Mergers began in 2016 with Victoria and Tasmania. This merger benefitted the community – the Tasmanian Deaf Society was tiny, its services limited.

The 2020 merger between Qld and NSW (including ACT) was a business move rather than a community need. Both were strong businesses. Both had a competent deaf CEO. Queensland had a lottery license so it became the head office with its CEO leading the newly branded organisation – Deaf Connect.

Deaf Connect began providing limited services in the Northern Territory in 2022. This is positive for the long-neglected NT deaf community.

The SA deaf community suffered deeply when the CanDo group took over their Deaf Society in 2007 without any community consultation. Their relationship with Deaf CanDo was always unhappy. For them it was a relief when Deaf Connect took over Deaf CanDo services last year, even though this takeover also happened without any community consultation.

The WA deaf community went through some trauma some years ago and some of its strongest deaf leaders withdrew from Access Plus WA Deaf. Victoria and WA were recently working in partnership and we all expected them to merge. We can only guess why the WA board decided to go with Deaf Connect instead of Victoria’s Expression Australia – again without any community consultation.

All these mergers with Deaf Connect do bring benefits to the community in the form of a strong, healthy business, a deaf CEO who understands the community, and a wider range of services available in more states.

But. There is a big BUT. One large organisation doing everything for almost all deaf people all over Australia is not healthy for our community. Control in too few hands is limiting. If mergers were necessary (and I’m not convinced they all were) it would be far better for us if Victoria, SA and WA merged. Power and control would be more balanced across the nation. Part of the problem was that for a long time deaf people were crying out to have deaf CEOs leading their Deaf Societies and Victoria was very slow to heed the call. They had opportunities but until this year they stubbornly kept appointing hearing CEOs. In taking so long, they probably lost SA to Deaf Connect.

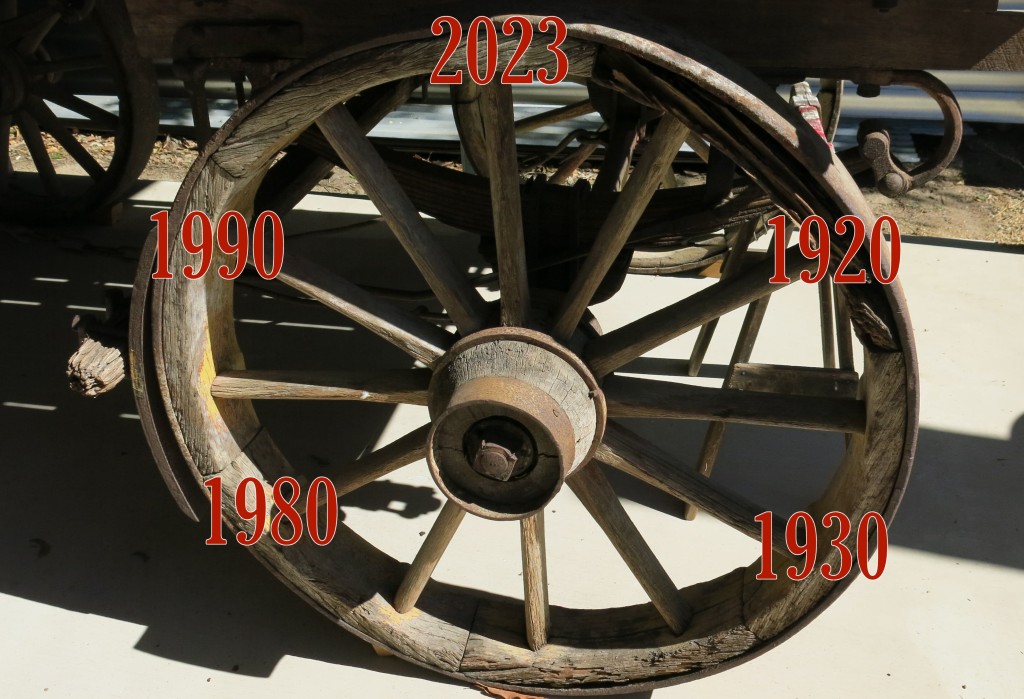

To me and, I suspect, many who remember the old style Deaf Societies with affection but clear eyes, the rise of Deaf Connect is a regressive step. It takes us back to a situation that is even worse than the 1980s and 1920s/30s. Not only have we lost our beloved deaf clubs and deaf buildings, we now have one large organisation doing everything for almost all of us, we have less control and fewer opportunities – and this is led by a deaf CEO. We can’t even just blame hearing people anymore.

However, we cannot lay everything at the door of the CEO. CEOs report to a board and at the end of the day it’s the board that approves the organisation’s direction.

Deaf Connect’s website tells us its board has twelve people. Nine men, three women. Nine hearing, three deaf. Nine with a business background, one teacher, one lawyer and one public servant. So Deaf Connect’s board is three-quarters male, three-quarters hearing and three-quarters business-minded. The direction Deaf Connect has taken is pretty much what we could expect of a male, hearing, business-minded board: business expansion, power and control. A healthy deaf community is not this board’s primary focus.

While we’re at it, let’s consider Expression Australia’s board. It has seven people. Three men, four women. Four hearing, three deaf. Five with a business background, one public servant and one working in the sports sector. This board has roughly equal gender and hearing/deaf balance, but is still primarily skewed towards business. So while we could expect Expression Australia to make business-minded decisions, we could also expect it to make gender-balanced decisions and work cooperatively with the deaf community.

Many people don’t seem to understand why the current situation is so bad for us. It is bad for us because, first, when the same organisation takes so many roles there are conflicts of interest. Deaf Connect provides services and it advocates for us. That’s a huge conflict of interest. It makes its money by providing services to us, so it benefits Deaf Connect to advocate for things that keep us dependent on its services. A clear example is the current situation with interpreting for people over 65. Deaf elders groups are advocating for the NDIS to include these people, but Deaf Connect is not. Why? Deaf Connect receives millions of dollars from government to provide interpreting services nationwide for people over 65. If deaf elders are successful in their campaign, Deaf Connect will lose this funding.

Another conflict of interest is between service provision and NDIS plan management and support co-ordination. Deaf Connect does all these things. When your NDIS support co-ordinator or plan manager is also a service provider, it benefits them to guide you to use their services rather than others. For example, there are many Auslan interpreting services. If Deaf Connect is your NDIS support coordinator or plan manager, do they encourage you to use other services such as Auslan Services or Sweeney Interpreting instead of Deaf Connect interpreting? I doubt it. They wouldn’t get your NDIS interpreting money if they did, so why would they?

To be fair, the NDIS allows this and some other service providers do it too. Service providers are supposed to keep these functions independent of each other but that’s a naïve and unenforceable requirement as long as the same organisation can do all these things. Many of us who were involved in designing the NDIS argued that plan management, support coordination and advocacy must be separate from service provision but we didn’t win that argument. It remains a serious flaw in the NDIS and needs to be fixed.

Second, the NDIS is meant to encourage diversity and choice. Although new businesses have appeared in the deaf space, they are small and specialised – e.g. interpreting, support coordination – and none can compete at Deaf Connect’s level. The only organisation that perhaps could is Expression Australia. We can only hope that they will establish competitive services in other states so that we at least have some choice. It is encouraging to see they are starting to do this in WA with a new office in Fremantle.

Third, many deaf people work for Deaf Connect. Deaf people still experience employment discrimination, so employment in a deaf organisation is an obvious pathway. Many also just prefer to work in a safe deaf space. Now that Deaf Connect has swallowed up so many state Deaf Societies, deaf people’s employment choices have shrunk. If they are unhappy working for Deaf Connect, where can they go? In the past they could move to any of five other states and work for the Deaf Society there. Now, if they don’t want to work for a smaller business, set up their own business, or work in a hearing environment, their only option is Expression Australia.

Fourth, with so many deaf people now working for Deaf Connect, there are a lot fewer deaf people who can object to anything Deaf Connect does. If they want to keep their job they must put up and shut up. This gives Deaf Connect incredible power and control over the deaf community. It is reminiscent of Victoria in the 1920s/30s, which Dr Breda Carty AO documented in her book, ‘Managing their own affairs: the Australian deaf community in the 1920s and 1930s’.

In that era, the Victorian Deaf Society’s CEO was a hearing man named Ernest Abraham. He could sign fluently and employed some deaf people, notably James Johnston (Dorothy Shaw’s father). Abraham often used James Johnston as the deaf public face of the organisation, and Johnston was forced to do whatever Abraham asked of him or risk losing his job. Modern Deaf Societies have also done this. They have used particular deaf staff as their public face when they wanted to communicate something to the deaf community. Access Plus WA Deaf did it when they used a deaf board member to announce their merger with Deaf Connect. The underlying psychological manipulation is: if a deaf person is telling us in Auslan, it must be ok.

Fifth, with so many deaf staff all over Australia, Deaf Connect could conduct ‘community consultations’ by ‘consulting with’ their deaf staff rather than the wider deaf community. This would enable them to claim they have consulted with the deaf community. Technically they would have because their deaf staff are deaf community members. But in reality their deaf staff are not free to express honest opinions if those opinions conflict with the organisation’s interests.

Sixth, Deaf Australia is being sidelined. Deaf Australia was for many years a high profile and influential national advocacy organisation, but in 2014 government changed its funding model and many disability advocacy organisations lost almost all their funding, including Deaf Australia. Since then it has struggled to maintain its work and profile. Instead of supporting Deaf Australia, as Deaf Societies did in the 1980s/90s, Deaf Connect has stepped into the breach and become the go-to organisation for advocacy. Deaf Connect and Deaf Australia do work together, but Deaf Australia really has no choice – while they continue to struggle with so little funding they have to work with Deaf Connect and maintain a cordial relationship in order to have any kind of say in advocacy issues.

This is similar to what happened in the 1920s/30s when deaf people and some hearing supporters established their own national organisation, the Australian Association for the Advancement of the Deaf. This AAAD only lasted a few years before it was crushed by Abraham and the Deaf Societies. Australia didn’t have another independent deaf-controlled advocacy organisation until half a century later when AAD/Deaf Australia appeared in 1986. We cannot afford to lose Deaf Australia. It is the only national organisation that puts our interests first.

Seventh, all this makes the deaf community feel and behave helplessly. When I talk about these issues with other deaf people, the most common response I get is: ‘the problem is the deaf community is so small’. In other words, what can we do, there aren’t enough of us!

So here’s a list of things we can do:

- Support diversity in the deaf ecosystem by using a variety of service providers, not just the same one all the time.

- Use independent NDIS service coordinators and plan managers so that you don’t feel pressured to use a particular service provider.

- Self-manage your NDIS plan. I do. If your plan is straightforward, self-management is not difficult, and you can ask a relative or friend to help you.

- If you self-manage your NDIS plan, do not tell anyone your plan number or anything else about your plan – to maintain your control of it. Contrary to what many service providers tell you, you do not have to tell them your plan number. They do not need it. They only need to send you an invoice for services you’ve used, and you need to make sure you have enough NDIS funds to pay them. If they insist you must tell them your plan number, go to another service provider who doesn’t.

- Support each other to build courage, confidence and skills and, if possible, go work for someone else so we can have an independent say in what happens in the deaf community.

- Support Deaf Australia – become a member, make donations, attend their events, serve on their board, do volunteer work for them, help them fundraise, tell Deaf Connect and any government contacts that you want Deaf Australia to represent you.

- Don’t just accept what any organisation tells you – investigate it, talk to other people about it, find out how accurate it really is.

- Tell the NDIA and government that you do not want organisations that provide services to also provide plan management, support coordination and advocacy.

- Talk to each other about these issues. Educate each other.

In the past we blamed hearing people running our Deaf Societies for patronising and controlling us. Now we need to be aware of new risks. It is good that our Deaf Societies now have deaf CEOs and many deaf staff. But this does not mean that everything they do is good for us.

[A note on the Auslan translation: This blog is translated by Chevoy Sweeney of Sweeney Interpreting. Her only role is to translate what I wrote. She had no input into the content. I would have chosen a deaf translator but it was difficult to find one who was both available and independent of the Deaf Societies – another impact of these mergers. I thank Chevoy for her work on the translation.]

Auslan translation:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1IYNMQCq5YILEKzMfSCIkLI56efE755YA/view?usp=sharing

Really thank you Karen for this detailed comment on the situation at hand… like you, I have been around for many of these changes (albeit as an ally and not a Deaf Community member). I agree that there is danger in the issues you have raised about one large organisation controlling all things ‘Deaf’. I don’t think it’s in the community’s best interest either. Yes, the community is small, yes, the community is complex but the community needs diverse services and one organisation cannot and should not do it all!!!

Thanks again Karen for you ever wise words!

LikeLike

Thank you for your article but I would like to point out few thing as a Deaf person from Western Australia.

First of all, If you wonder why lots of us are very accepting when it come with Deaf Connect sudden merger with Access Plus WA.

1. We (the community) have been going through struggles with two previous CEO which have been ignoring our community requests and concerns over period of time.

2. Both of previous CEO have decide not to support and keep other volunteer organisation together to support – WADRA/WAAD/ASLIA WA

3. First CEO told community that they’ll be moving to new location and promise to work together to find new better location to bring everyone back together within 2-3 years of time but now it have way past this period of time and we have seen ZERO action from them then second CEO “tried” but all of our concerns and questions falls on deaf ear (puns intended).

4. CEO told victim to move on with their legitimate concerns where it is actual base on facts not baseless accusation.

5. Community have lost their trust and faith in Deaf CEO at the point where group of people decide to organise “Deaf Social Night” mainly because lack of action/understanding from Deaf CEO

6. Previous two CEO doesn’t align/respect/follow Perth Deaf Community’s unique value when it come with community that we all are truly together as one.

——————————————————————-

Also look at the timeline with Expression Australia set up office in Fremantle which took EVERYONE surprises so if you think Deaf Connect is not doing the merger correctly without letting community know (But they did it for a right reason) comparing to Expression Australia set up office for what reason? Aren’t they supposed to be “Partnership” with Access Plus WA so why didn’t they organise to use each other resource effectively instead of set up new office? think about it.

I understand your concerns about one big corpo which could end up a soulless machine “supporting” all over the australia for Deaf people but there’s a lot more to it than just “Deaf connect merger with Access Plus cause Deaf community worries about their merger” – WA Deaf community are very very tired with our previous CEO who’s very out of touch with the community and do not listen (pun intended) to Deaf community.

————————————————————————

I would like to confirm that Deaf Connect do encourage their clients to use other service instead of their own.

Disclaimer – I am not working for Deaf Connect and/or Expression Australia but I am a concerned Deaf citizen from WA Deaf community.

I do not want to share my name for personal reason where I don’t feel safe enough to give out my name publicity where I could get backlash from our previous CEO given our experience with them for few years.

Please correct me if any of my information above might be wrong but this is from what I know at top of my head.

———————————————————————–

I agrees wholeheartedly where we need to support Deaf Australia a lot more given they’re not getting any funds from government but this is definitely something we should raise it to Deaf Connect.

LikeLike

Thank you very much for sharing your perspective on this. It is important that we all talk about the issues and your contribution really helps the discussions.

I understand why you don’t want to identify yourself – this is one of the problems with these issues, people don’t feel safe to discuss them. Your perspective is as important as anyone else’s. Thank you for sharing it.

I understand that there are often issues with particular CEOs. One of the problems with all this is that we like some CEOs (either deaf or hearing) more than others and some will do a better job than others. However, the changes that the mergers bring are structural changes and long-lasting. CEOs come and go but structural changes are long-term. They will still be there long after a good CEO moves on and the community might be very unhappy with the next CEO but will be stuck with them because of the structure that is in place. It’s important to get the organisational structures right. It’s easier to change CEOs than organisational structures.

LikeLike

A follow up on my reply to Deaf person from WA.

I realise I didn’t address your comments about the Expression Australia office in Fremantle. I don’t know anything about the timing of when they established it, I only know they’ve recently established one there and I thought it was after the announcement of the WA and DC merger as I heard about it only in the last couple of weeks. Perhaps you could provide some more information about the timing?

I need to explain more about what I mean about structures. I also want to clarify that the article was not only about WA. The WA and Deaf Connect merger is what prompted me to write it, but it is about all of the mergers, not just WA. As the article says, in some ways the mergers are understandable, eg as well as WA, SA also struggled for a long time before DC ‘rescued’ it.

I understand there are often issues with particular CEOs. I understand some people disliked the last WA CEO. I’ve also been told privately that some people did like them. It has always been this way with pretty much all organisations and always will be. When I was CEO of Deaf Australia some people liked me and some people didn’t. That’s how it goes.

I didn’t talk about specific CEOs and issues with them in my article because I wanted us to focus on the big picture issues that are there regardless of who is the CEO. If we have strong structures that put the power and control mostly in the community, then it is easier to deal with problem CEOs. If we don’t have those strong structures, we might have a great CEO who does everything right in our eyes (which is unlikely – it’s impossible to please all of the people all of the time) but that CEO is very powerful and has enormous control over the community, and when that great CEO moves on we might get a CEO who uses this power and control in destructive ways.

The issues I identified in my article are structural issues. Eg, employment – one big organisation instead of six small organisations greatly reduces our employment options. That’s a structural issue and will be there regardless of who is the CEO.

You mentioned that DC does encourage their clients to use other services instead of their own. That’s good to see. However, the fact that one organisation can do plan management and support coordination as well as provide services is a structural issue. When a new CEO comes in they could stop encouraging clients to use other services – because there is nothing in the structure that guarantees this separation of roles. This is an example of what I mean when I say we need to be aware of risks. It might not be a problem right now, but there is a big risk it will be a problem at some time.

The Deaf Australia funding issue is a really big problem and the community does need to come up with a way to resolve it. It would be good if service providers – not just Deaf Connect – contributed some funds to Deaf Australia but the problem with that is such funds are never really free of strings. It puts an obligation on Deaf Australia to do things to keep their funders happy. Back in the 1980s/90s when the Deaf Societies all contributed some funds to AAD, they didn’t put particular strings on it but they sometimes made it clear that they weren’t happy with what we were doing with their funding.

Most funding is made available for particular projects that the funding organisation approves of, but Deaf Australia really needs funding that enables it to advocate for us free of any pressure to please anyone other than the deaf community.

One way to guard against obligations to keep the funders happy is for funding to be given with a contract that specifically says the funder makes no claims on Deaf Australia and Deaf Australia is free to use the funding however they wish. But I’ve never seen a contract that says that. When I worked for Deaf Australia and we had funding contracts with government, we had to agree on what we would do with the funding. Our contracts were quite broad and gave us a lot of scope – as long as we sent in satisfactory reports about how we were spending the money and how we were meeting the contract agreements.

However, during the early 2000s under the Howard government, our funding contract (and every other organisation’s funded from the same pot of money) included a clause that required us to notify the funding department of any campaigns and media releases several days (can’t remember the exact time frame, I think in some cases it was a week) before we sent out the media release – and we had to send them a copy of the draft media release. This was referred to as a ‘gag’ clause because it effectively did gag organisations that wanted to criticise the government. It wasn’t a big problem for us at the time but it was for some organisations eg ACOSS. In 2007 when the Rudd government came in, the first thing our funding department did was to send us all a letter telling us our gag clause was cancelled. So, without strong structures that make organisations like Deaf Australia truly independent, we are always at the mercy of the government of the day or the organisation/s funding us.

How can we make Deaf Australia truly independent? The only way really is for the deaf community to fund it. That means we all need to make an annual financial contribution, and we all need to be more actively involved with running, supporting and overseeing it. Like how we fund our unions with our membership fees and how we fund our government with our income tax, GST tax etc. Are we willing to do that for Deaf Australia? I am, and I know some other people are, but are enough of us?

We need to move on from the old welfare mindset where others do things for us and we don’t contribute. The welfare mindset means we give up control over our own lives. This is a big reason we now have the NDIS – its original aim (not currently being wholly met) is to give choice and control to us. We need to take on responsibility and control for ourselves. That means funding Deaf Australia ourselves. Will we? We need to have a really big conversation about this in the deaf community. I don’t have all the answers and I really want to see the deaf community tackle this issue together. Maybe I need to write a whole new article about it! I sort of have already with this reply to your comment! Maybe we need a national conference about it!

LikeLike